In speaking to and reading accounts by Anglican Christians who have been inclined toward reconciliation with the Roman Church, but who hesitate on the threshold, there are various stumbling blocks that come up. I don't think any of these are trivial, although some are obviously of greater importance than others.

For one person it may be questions about Catholic dogmas: Papal Infallibility, the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin, or some other defined doctrine. For others it could be scandalous behavior in the Catholic Church that renders her less attractive.

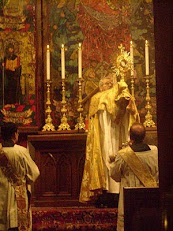

Still others are hesitant to abandon the very things that nourished their faith in Christ: a parish that is focused on Christ and living out the Gospel, a church that has been the scene not only for their own faith life, but that of generations of their family, or the beautiful liturgy for which modern Anglican churches are rightly praised. "How," a person might ask themselves, "will I continue if I am deprived of the worship that has been the vehicle for the grace that has brought me to this point?"

Of course, the promise of the Pastoral Provision and the Personal Ordinariates is that such an Anglican Christian needn't give up anything from their past that is true and beautiful, that such practices will be welcome in the Catholic Church. Nevertheless, the fact that something is welcome doesn't mean it will in fact happen! If a small number of people are received into the full communion of the Catholic Church and do establish an Ordinariate Community, that doesn't mean that they'll have a choir, or organist, or books. "We'll never have evensong like we used to," they might think.

Well, it's true, things will be different. But not necessarily worse!

For many, the part of the Daily Office that is most familiar, and most cherished, is Choral Evensong. Pope Benedict himself was so entranced with the service at Westminster Abbey during his visit to England that he invited the choir there to join him at St. Peter's in Rome for the feast of Ss. Peter & Paul. But Evensong as it is today is not how it originally was celebrated. Imagine the same words, but there is no Anglican Chant and no hymns. Seem impossible? And yet, that was how Evensong was celebrated for nearly 100 years after the first Book of Common Prayer was issued in 1549.

When Cranmer and the royal authority issued the Daily Offices as part of the Prayerbook, they were not a new creation; rather the Daily Officers were an adaptation and a simplification of the Divine Office of the the Medieval Church. What was also adapted and simplified was the music for the Office. We have one example from that time in the Book of Common Prayer Noted by John Merbecke, but his was not the only adaptation. In addition to this adaptation of plainsong, there were simple harmonies, often in the form of fauxbourdons that were employed. And of course, there were more complex pieces written by some of the great musicians of the age, such as Thomas Tallis and William Byrd. Nearly all of this was a capella, because the use of organs in churches was fairly rare; organs were more typically found in private homes.

The parishes, as opposed to the cathedrals, tended to have the simpler music, which also made it possible for the lay people in the congregation to join in. And this example from the early days of specifically Anglican services may well be a help for new Ordinariate congregations today. While services of chanted Evensong may not be hosted soon on the BBC's Choral Evensong broadcast, it will provide for the most important aspect of any liturgy: the worship of God and the building up of His people.

First, many people may not have even heard an a capella service. As an example, I would point you to the web site of the Compline Choir. This choir began in 1954, and since 1956 has been singing the office of Compline at St. Mark's Episcopal Cathedral in Seattle every Sunday. The service has been broadcast continually since 1960, and now is available as Podcasts as well. The most recent podcast I listened to, from October 14th, was entirely a capella and is a wonderful example of the most important instrument we can employ in the praise of God: the human voice.

Of course, any group starting out will not sound like the Compline Choir the first time out; but that hardly matters. The key resource, I think, that people need is to have the chants available. That resource, fortunately, is readily to hand: The Saint Dunstan Plainsong Psalter. This book, which is actually more than just a psalter, contains the American version of the Coverdale Psalter along with the usual canticles from Morning and Evening Prayer. Each of the psalms is set to one chant melody, while the canticles are set to multiple chant melodies. There is also a set of Old Testament canticles to supplement the appointed ones for Morning Prayer, with both festal and ferial settings.

I use St. Dunstan's Psalter daily to pray the office, but also used it as a source for compiling the Compline service we used at St. Athanasius on Maundy Thursday, at the end of adoration following the Mass of the Lord's supper.

Obituary of a very failed Pontificate

-

"Nun khre methusthen kai tina per bian ponen, epei de katthane

Mursilos."Such would have been the reaction of the unchristianised Greeks.

But for us, for t...

8 months ago

No comments:

Post a Comment